There was no direct correlation between the Depression and the chances of success of the radical Right. The Depression crisis had, it is true, led to Hitler’s triumph. But Mussolini had come to power in Italy almost a decade before the slump, while in some countries fascism only emerged when the Depression was subsiding. Furthermore, other countries (notably Britain and, outside Europe, the USA), although suffering severely from the Depression, still did not produce any significant fascist movement. Only where the social and political tensions created by the Depression interacted with other prevailing factors – resentment about lost national territory, paranoid fear of the Left, visceral dislike of Jews and other ‘outsider’ groups, and lack of faith in the ability of fragmented party politics to begin to ‘put things right’ – did a systemic collapse occur, paving the way for fascism.. Italy and Germany turned out to be, in fact, the only countries where home-grown fascist movements became so strong that – helped into office by weak conservative elites – they could reshape the state in their image. More commonly (as in eastern Europe), fascist movements were kept in check by repressive authoritarian regimes, or (as in north-western Europe) offered a violent disturbance to public order without the capacity to threaten the authority of the state. Fascism’s triumph depended upon the complete discrediting of state authority, weak political elites who could no longer ensure that a system would operate in their interests, the fragmentation of party politics, and the freedom to build a movement that promised a radical alternative.

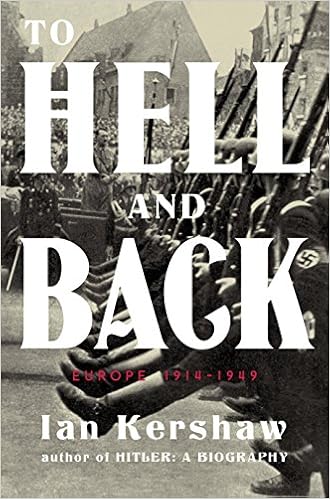

-Historian Ian Kershaw in

No comments:

Post a Comment